I started to experience symptoms about 16 years ago. I was going through hard times. I lost my two brothers and my mother, I lost my business and my home.

In these moments I was not a good person. Anger was my reaction to everything. I was tearful and irritable. I could not cope with my anger. It was exhausting but I didn’t know that it was depression. Only years later, I learned that it was MDD.

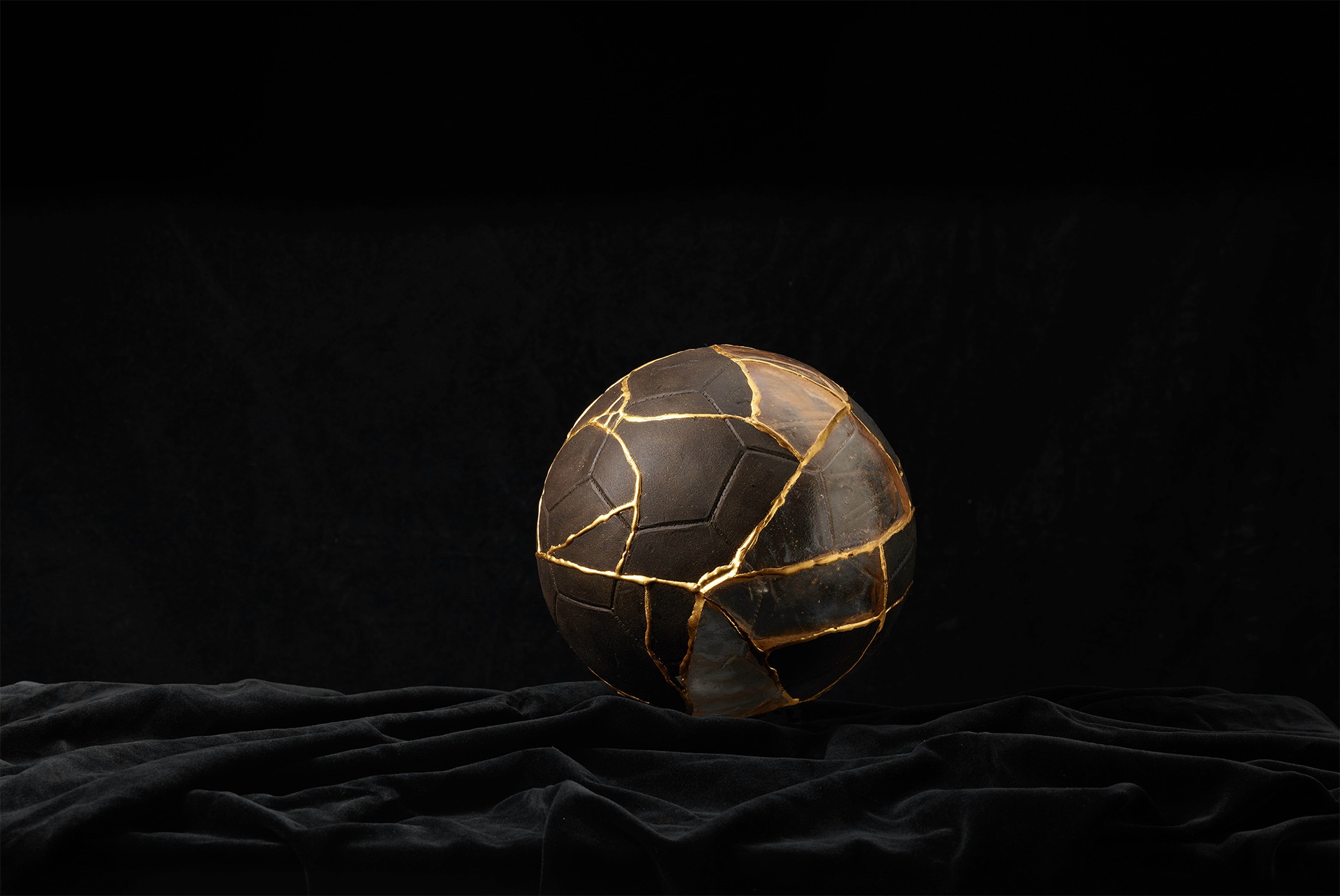

For me, depression is a monster. An ink-black octopus with tentacles that hit precisely on your painful points. Even when you have a small sprout of a desire to do something, the octopus rises and just breaks it with its tentacles. It is a ruthless enemy.

I grew up in a big family where I could not openly express my feelings. Even now, after many years trying to talk about my inner feelings to specialised doctors and therapists, it is difficult for me to find the right words.

My MDD has affected my relationships with others. Honestly, for five long years I was suspicious of other people. I withdrew into myself, avoided close relationships. I threw out my old SIM card, I did not want to talk with anyone.

The children tried to help me, especially my son. When my daughter went to work in South Korea, they decided a change of environment could help me. So they paid for my flight and treatment. In fact, the language barrier with doctors resulted in incorrectly prescribed treatment that worsened my condition.

As a believer, I have my faith. It has been with me throughout my journey. When there is this terrible emptiness and no desire to live, I rely on prayer.

As a mother, I dream of not being a burden to my two beautiful children. And I dream of my own house. Having lost it 16 years ago, I still wander around in exile in rented apartments.

I realise that there are a lot of unresolved problems inside me. I am working on myself, but it is hard. To others experiencing MDD, be grateful when family and friends come to help because without warmth, care and support it is difficult to recover.